Roving Exhibition – Exploring Traditional Music of Japan

Text / Videos / Pictures: Professor Christopher Pak (Head of Academic Studies in Music, The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts)

Japan is one of the most popular locales among holiday travelers. Television drama series, electronic games and manga from Japan have numerous fans around the world, while Japanese cuisine is also highly welcome globally. Japan is a unique country, where flourishing popular cultures also develop side by side with traditional performing arts that have been preserved and transmitted for centuries. Long before the concept of “cultural heritage” has assumed its role in our common sense, Japanese society has already secured a multilayer system for the transmission of traditional performing arts that requires the efforts from laymen to top authorities. Such perseverance and persistency to heritage have demonstrated a unique character in Japanese culture. The introduction to traditional Japanese music shown below aims at offering an extraordinary travel experience and enabling you to understand Japanese culture from a different perspective.

![]() To start the extraordinary inside tour to Japan , please click the following tabs and view the full version of the demonstration performances.

To start the extraordinary inside tour to Japan , please click the following tabs and view the full version of the demonstration performances.

Traditional Japanese Music: Genres and Transmission of Hogaku

Traditional Japanese instrumental music was closely linked to music from northeast Asian countries like China and Korea. However, these instruments with foreign origins have already become parts of a local music tradition that has gone through centuries of development and transformation, representing a unique Japanese artistic style.

Since the end of the Shogunate Era and the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Western culture has become increasingly influential in Japan. Elements of Western music were introduced to Japanese music, resulting in the emergence of various classical, serious and popular genres as well as performance practices. To the other end of the spectrum are those traditional music genres rooted in royal court and local communities that have been nourished for generations.

Consequently, a system for the catergorisation of music genres is being adopted, with the term “Hogaku” referring to traditional Japanese music and the term “Music” referring to newly emerged musical genres influenced by Western culture.

Hogaku still being performed today includes several major categories:

- Court, religious and festive music: including Gagaku and ritual music of Shinto

- Regional vocal music, instrumental music and related genres: minyo, jiuta and sankyoku, as well as music for instruments like koto and shakuhachi

- Theatrical genres: Noh-Kyogen, Kabuki and Bunraku

Since the end of the Second World War, Japanese government and local communities have put great efforts on the revival of traditional culture, leading to the enactment of the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties (Bunkazai Hogoho) in 1950. One of the most important aspects of the Law is the designation of Intangible Cultural Properties (including artistic genres like music and theatre) and related preservation policies, a concept comparable to the recent notion of “intangible cultural heritage”. Since 1955, the Minister of Education has recognised individuals or groups of individuals who are masters of the designated intangible cultural properties, commonly known as National Living Treasures.

Characteristics of Traditional Hogaku

- Mainly monophonic texture

- Mainly with rhythm in duple meter

- Great varieties in tempo among different music genres or within the same piece of music

- Form is influenced by the concept of “jo-ha-kyu”. Music typically starts in unmetered rhythm with slow tempo, gradually becoming faster with regular pulses

- Emphasises contrast in tone colour and dynamics; frequent use of microtones, particularly in music for wind instruments

- Two pentatonic scales are most typical: in scale (miyakobushi scale) with semitones and yo scale (minyo scale) without semitone

Gagaku: Ceremonial Music and Dance Established at the Imperial Court for More Than a Thousand Years

Gagaku is the genre of Hogaku with the oldest history, established at the royal court since the Azuka-Nara Period for over a thousand years. Gagaku was linked to the Chinese concept of “refined music” (yayue) influenced by the teaching of Confucius, though the Chinese and Japanese concepts of “refined” music were not exactly the same. After centuries of Japanisation, Gagaku is still performed in court and Shinto rituals and ceremonies today. Currently Gagaku in the royal court is performed by the staff from the Music Department of the Imperial Household. Gagaku was inscribed onto the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the UNESCO in 2009.

Current repertoire of the Japanese Gagaku consists of three categories:

- Music and dance employed in imperial and Shinto ceremony (Kuniburi-no-utamai): repertoire of indigenous origin, including Mikagura, Azuma-asobi, Kume-mai and others

- Music and dance of foreign origin from Asian mainland: the two main categories are Togaku and Komagaku; performance styles are divided into Bugaku-samai (Togaku, or Dance of the Left), Bugaku-umai (Komagaku, or Dance of the Right) and Kangen (pure instrumental music)

- Accompanied vocal music created during the Heian Period: Saibara and Roei

Well known Gagaku pieces include Etenraku (Kangen), Ranryoo (Togaku), Nasori (Komagaku) and others.

Kangen

Kangen

Bugaku

Bugaku

Gagaku: Musical Instruments

There are three types of musical instruments used in Gagaku, including:

- Winds: three transverse flutes (kagurabue, ryuteki, komabue), hichiriki, sho

- Strings: wagon (or yamata-goto), so (or koto), biwa

- Percussion: shakubyoshi, kakko, san-no-tsuzumi, taiko (gagu-taiko, dadaiko), shoko (tsuri-shoko, oshoko)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below are brief introductions to two unique instruments employed in the performance of Kangen and Togaku:

|

|

Sho |

|

|

Hichiriki |

|

Hogaku: Traditional Japanese Musical Instruments

| During the Tokugawa Period, artistic preference of public audience in places like Edo (Tokyo) became more crucial in influencing the development of music performance. Koto, shamisen and shakuhachi gradually became the most popular traditional musical instruments, first as accompaniment for various vocal genres and folksongs, later developed into specific performance schools. | ||

| Koto | ||

|

||

| Koto was first introduced from China in Gagaku. The construction and performance practice of koto had gone through various changes in history (court koto of the Asuka-Nara Period, tsukushi-goto of the Muromachi Period and sokyoku of the Edo Period), however, the instrument retained a 13-string design. Development of the sokyoku tradition was attributed to Yatsuhashi Kengyo (1614-1685) and he was generally considered the pioneer of modern koto music. Currently Ikuta-ryu and Yamada-ryu are the two major traditions of Japanese koto music, established by Ikuta Kengyo (1656-1715) and Yamada Kengyo (1751-1817) respectively. |

||

| Since the Meiji Period, various new designs of koto were being introduced. The most notable change was the 17-string koto developed by Miyagi Michio (1894-1956). Koto with 20 to 30 strings were also developed by artists like Nosaka Keiko (1938-2019) since the time of Miyagi. Today, teaching of koto in music conservatories in Japan is still restricted to 13- and 17-string koto, focusing on traditional repertoire. Haru no Umi (The Sea in Spring) by Miyagi Michio remains one of the most famous works for koto. |

|

|

| Shamisen | ||

Two different types of shamisen: chuzao (middle-neck, above) and hosozao (thin-neck, below) Two different types of shamisen: chuzao (middle-neck, above) and hosozao (thin-neck, below) |

||

| Sanxian was first brought to Ryukyu (Okinawa) during the late 14th century (Ming Dynasty in China). Named shamisen, the instrument was mainly used in accompanying vocal music. In the 16th century the instrument was introduced to mainland Japan, originally played by blind monks who used biwa to accompany narrative singing. During the Edo Period, shamisen became the most popular instrument to accompany vocal genre known as kumiuta, later expanded to genres like jiuta and naguata. As a popular instrument, shamisen of different sizes have been developed to meet the performance needs of specific genres. |

||

| Shamisen music does not exclude innovative ideas. For instance, Tsugaru-shamisen incorporates many lively new techniques in its music, making it very popular among young audience in recent years. Performers like the Yoshida Brothers even add popular and world music elements in their works, transforming an instrument only for traditional vocal genres into a household name. |

|

|

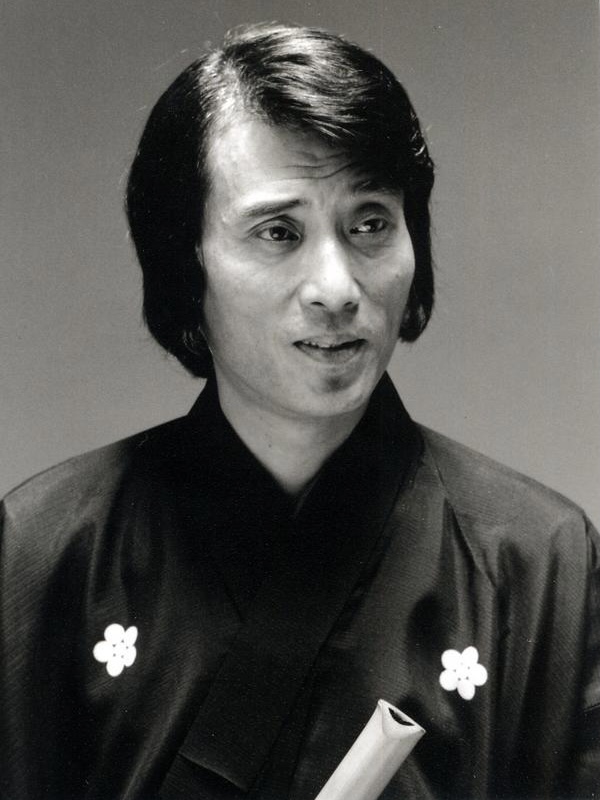

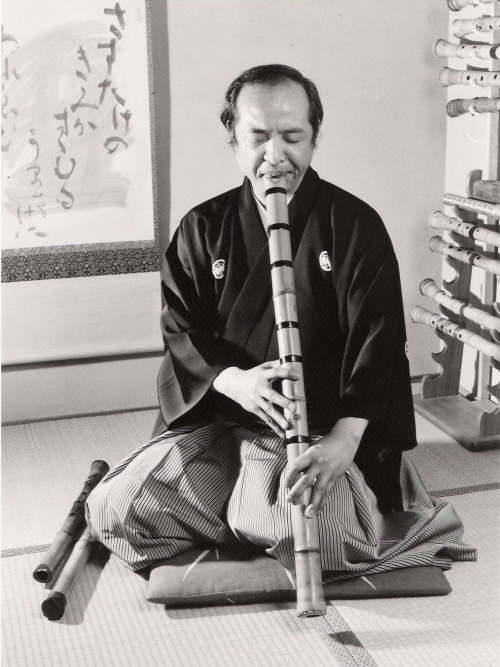

| Shakuhachi | ||

|

||

|

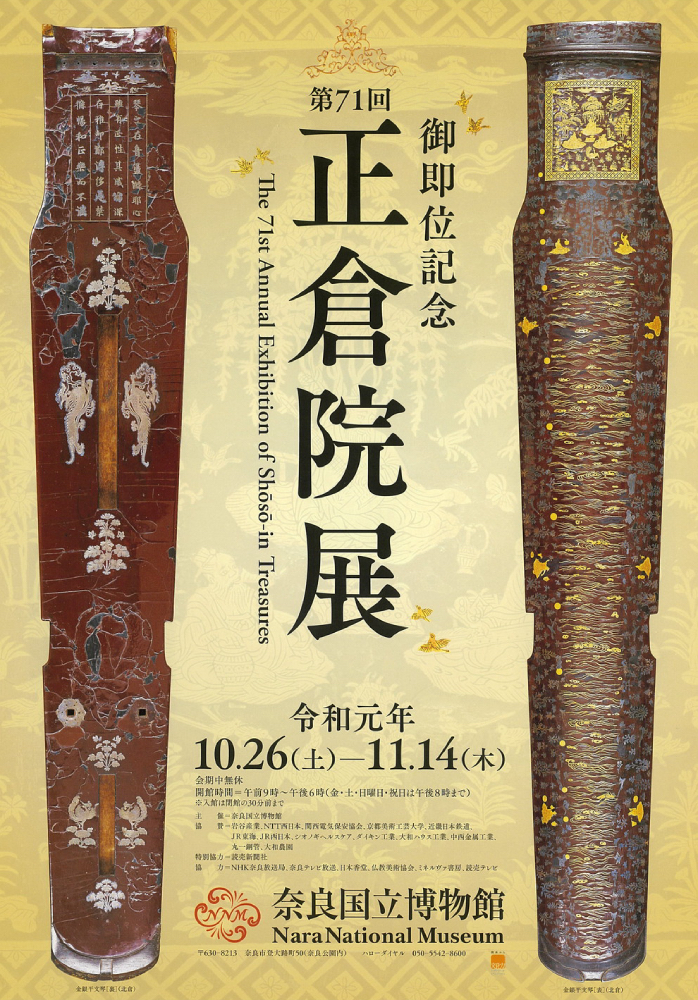

Shakuhachi was also brought to Japan as an instrument in Gagaku, though the instrument was dropped from the ensemble after reform of the genre in the Heian Period. Eight shakuhachi dated back to the Tang Dynasty are still stored in the Shoso-in treasure house of Todaji temple in Nara. During the Kamakura Period, a one-segment shakuhachi was performed by mekura hoshi (blind monks). Another thin shakuhachi named tenpuku was popular in Kyushu from the Muromachi through the Edo Periods. The modern shakuhachi can be traced back to music performed by beggar-monks called (monks of nothingness) of the Fuke sect of Zen during the Edo Period. The imperial government abolished the sect in 1871. As a result, Buddhist monks began teaching people to play the shakuhachi.

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

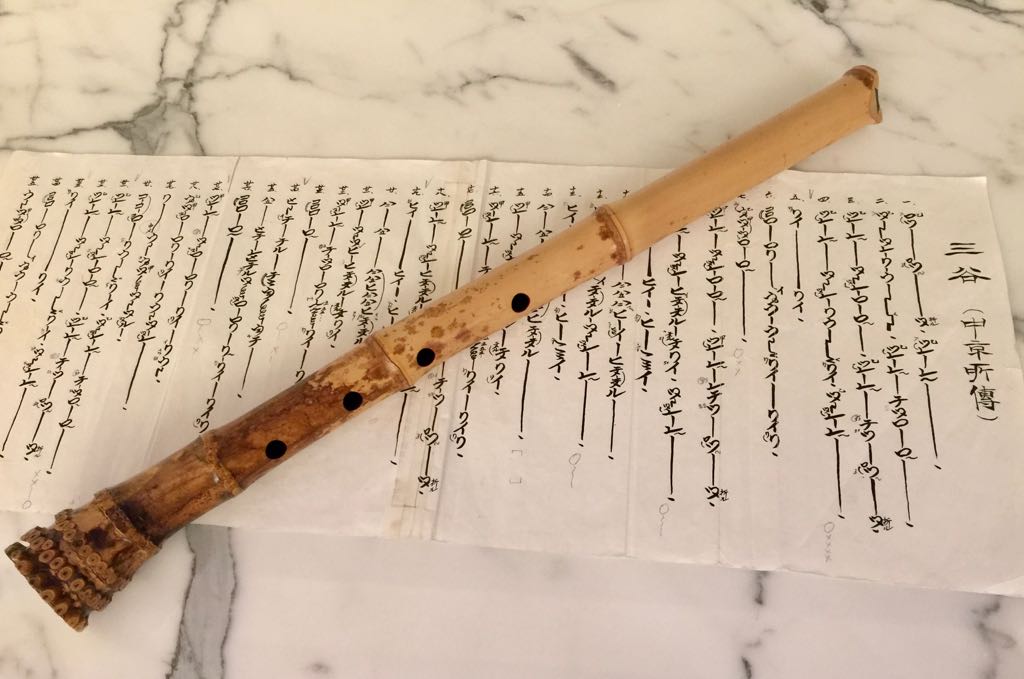

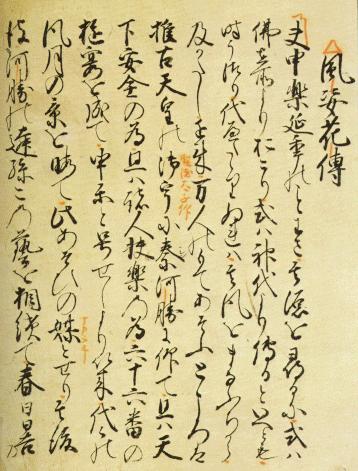

Passing to the Next Generation

|

Traditional music in Japan relies mainly on oral transmission. Although written music notations now exist for all genres, most traditional scores are based on syllables to represent the music notes and each instrument has its own unique notation system. Another interesting aspect about the transmission of traditional music in Japan is the secrets kept by renowned masters. From music scores, performance practices to written treatises, only worthy students or successors to the schools would be given the privilege to know these secrecies in the past. For example, the famous treatise Fushi Kaden written by the Noh master Zeami in the early 15th century was only known to the public by the late 19th century. However, advancements in technology and changing social conditions in contemporary society have brought many changes to the methods in transmitting traditional music. Today, many universities in Japan have established a department teaching traditional music, while traditional ways of teaching are still preserved by some masters.

|

“Fushi Kaden” by Zeami (early 15th century) |

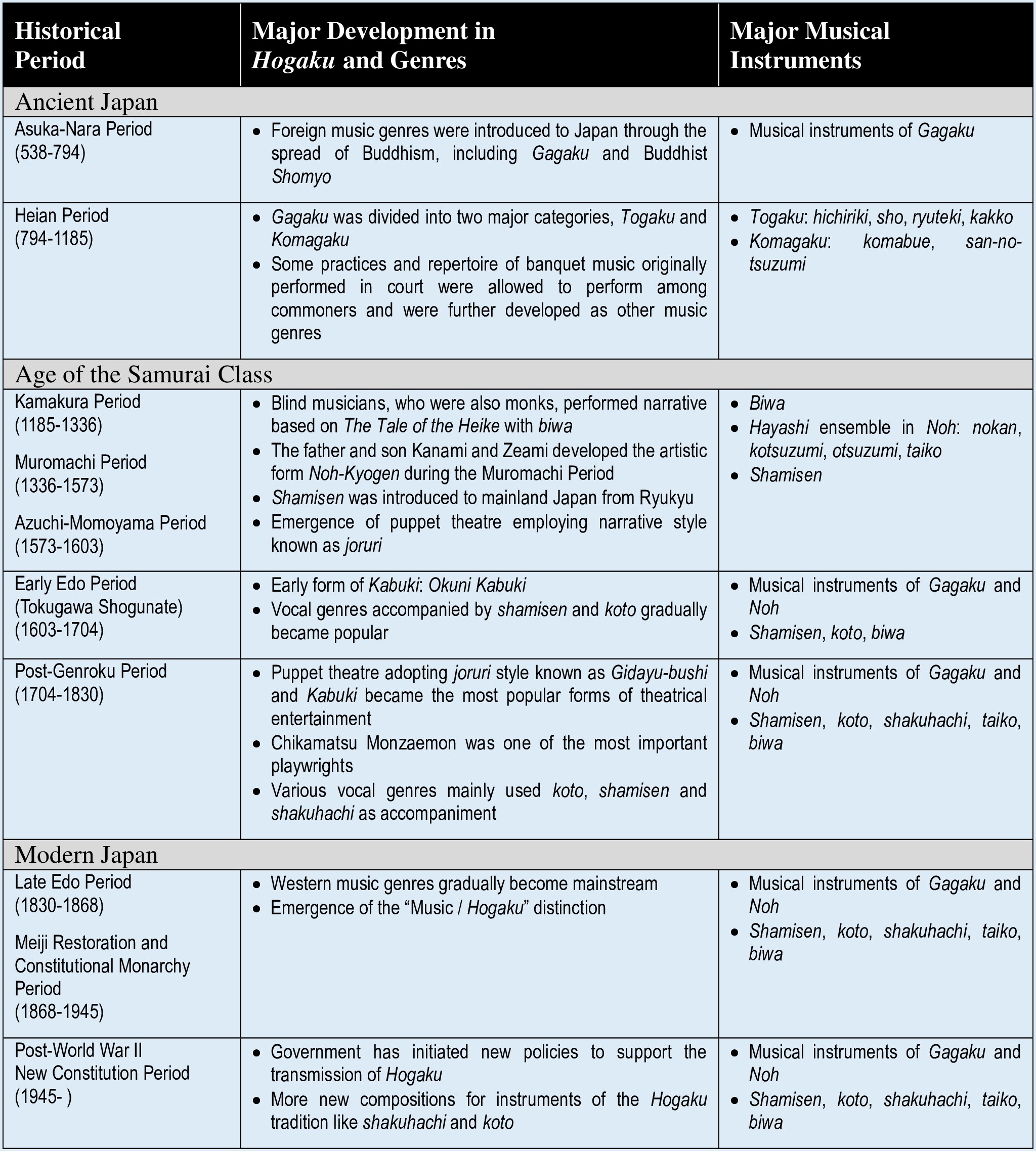

Hogaku: History and Development of Musical Instruments

|

||

|

Musical instruments stored in the Shoso-in treasure house of Todaji temple in Nara: |

||

Shakuhachi with birch tree bark (left), shakuhachi (middle) and stone shakuhachi (right) Shakuhachi with birch tree bark (left), shakuhachi (middle) and stone shakuhachi (right) |

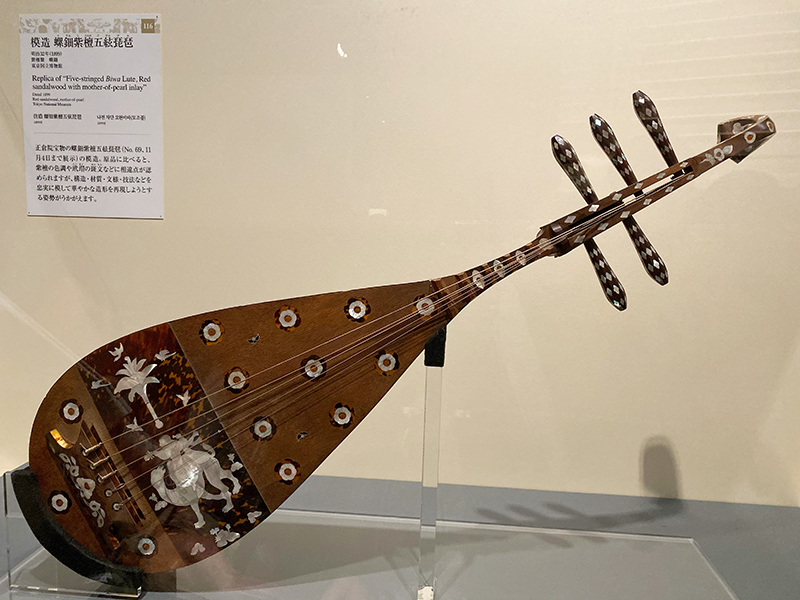

Biwa of shitan with pearl inlay: front (left) and back (right) Biwa of shitan with pearl inlay: front (left) and back (right) |

|

Genkan of shitan with pearl inlay: front (left) and back (right) Genkan of shitan with pearl inlay: front (left) and back (right) |

Five-stringed biwa with pearl inlay (replica) Five-stringed biwa with pearl inlay (replica) |

|

Kin with gold and silver cutouts shown in the leaflet of the 2019 Shoso-in Exhibition, Nara |

||

Final Words

On one hand, transmission and development of Hogaku are supported by government policies as well as social structures of transmission deeply rooted in historical tradition. Teaching of Hogaku is also successfully adopted to the modern education system. On the other hand, preservation of tradition does not reject the introduction of new creative ideas and performance practices. In fact, the addition of modern and popular music elements has given a vibrant life to Hogaku, enabling it to reach a wider public. People should be inspired by such perseverance and openness to tradition in understanding of our own traditional musical culture.

Tsugaru-shamisen group “Yoshida Brothers”: Yoshida Ryoichiro (left) and Yoshida Kenichi (right)

Demonstration Performances

|

Itsuki no Komoriuta (The Itsuki Lullaby)

Itsuki Village is located in Kuma District of Kumamoto Prefecture. There are numerous versions of the folksong The Itsuki Lullaby. The lyrics express the feeling of a poor young girl who worked as babysitter in a rich family. The melody is built on the typical in scale and the music is often heard on various solo instruments such as shakuhachi. Kojo no Tsuki (The Moon over the Ruined Castle) Originally written for junior high school students, The Moon over the Ruined Castle was composed by Taki Rentaro (1879-1903) in 1901. The melody and lyrics were inspired by several ruined ancient castles. The melody also features the typical in scale and the music becomes very touching when being played on a shakuhachi solo. Shakuhachi: Yeung Kwong |

|

Yosakoi Bushi (The Yosakoi Ditty)

Popular since the Edo Period, the folksong The Yosakoi Ditty tells the gossip about a monk who was seen purchasing a hairpin for young woman in a shop near the Harimaya Bridge in the City of Kochi. The Yosakoi Matsuri is the most important festival held every August in Kochi. This version is played on a koto solo. Koto: Etta Lee |

|

Haru no Umi (The Sea in Spring)

Written by Miyagi Michio, a blind koto educator, performer and composer, in 1929 for koto and shakuhachi, The Sea in Spring was inspired by his childhood memory about a small fishing village in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture. The work is popular in Japan during the New Year festive period. Koto: Hsu Su-ping Shakuhachi: Liu Ying-jung Excerpt from “Song of Crescent Moon” concert by Hana No Waon |

|

Hyojo no Choshi (excerpt)

Choshi is the introductory piece in Bugaku-samai (Togaku) repertoire. Each of the six modes used in Togaku, including hyojo, has its own choshi to show the characteristics of the mode. Hyojo no Choshi opens with sho, hichiriki and ryuteki. The free-rhythm on sho is featured in this excerpt. Sho: Loo Sze-wang |

|

Etenraku (Hyojo) (excerpt)

The most well-known Gagaku piece among all Togaku and Kangen repertoire, Etenraku is still often be played during traditional weddings and festival days at temples and shrines. This excerpt features the opening part of the piece played in the hyojo mode by hichiriki. Hichiriki: Wu Chun-hei |

|

Tsugaru Jonkara Bushi (Tune of the Tsugaru Jonkara)

Tune of the Tsugaru Jonkara is one of the three most famous folksongs from Aomori Prefecture, often accompanied with the Tsugaru-shamisen. The melody is a variation of the folksong Tune of the Shinpokodai Temple from Niigata Prefecture. The music is also often heard on a Tsugaru-shamisen solo. This solo version is played by Hirohara Takemi, who is the Iemoto (Grand Master) of the Hirohara Shamisen School (Hirohara Sangendou). He was the Big Prize category winner at the National Tsugaru-shamisen Concours Osaka Contest in 2002. Tsugaru-shamisen: Hirohara Takemi Excerpt from “Taiwan-Japan Music Exchange Concert” by Chiayi Traditional Orchestra |

|

Nanbu Tawara Tsumi Uta (Song of Storing Tawara from Nanbu)

Tawara is a cylindrical straw container used by Japanese farmers to store rice after harvest. Song of Storing Tawara from Nanbu is a folksong from the Sannohe District of Aomori Prefecture (a part of Nanbu Domain during the Edo period) in Northeast Japan. The lyrics paint a joyful picture of farmers busy in filling up and storing tawara in the godowns after a bumper harvest. It is a song of celebration. Tsugaru-shamisen: Hirohara Takemi Japanese folk singer: Kakizaki Takemi Taiko: Ueda Shuichiro Excerpt from “Taiwan-Japan Music Exchange Concert” by Chiayi Traditional Orchestra |

|

Red Body

Red Body shows the vivid character of Tsugaru-shamisen through the accompaniment of guitar and cajon in the work. The music is a fine blend of traditional musical style and modern expressions. It was written by Hirohara Takehide, who has been a disciple of Hirohara Takemi for many years and is currently Director of the Hirohara Shamisen School in Taiwan (Taiwan Hiroharakai). Tsugaru-shamisen: Hirohara Takehide Excerpt from Tsugaru-shamisen Taiwan Hiroharakai Sixth Anniversary Concert |

| For further understanding of traditional musical instruments from Japan, please visit the Traditional Music Digital Library presented by the Senzoku Gakuen College of Music (in Japanese and English). |