Music Exhibition - A Rendezvous with the Guqin

Text / Videos / Pictures: Dr. Tse Chun-yan (PhD in Ethnomusicology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong)

With a history dating back around 3,000 years, the qin, or guqin as this Chinese zither is more commonly called today, is one of the oldest plucked musical instruments in China. The guqin ranks first among the traditional four arts of Chinese literati, along with chess, calligraphy and painting. Occupying a distinctive position in Chinese culture, the art of guqin music was designated a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by the UNESCO in 2003 and has thus been recognised as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage. This exhibition will bring you a wonderful world of guqin music.

![]() Please click the following tabs and view the full version of the demonstration videos.

Please click the following tabs and view the full version of the demonstration videos.

What is Guqin?

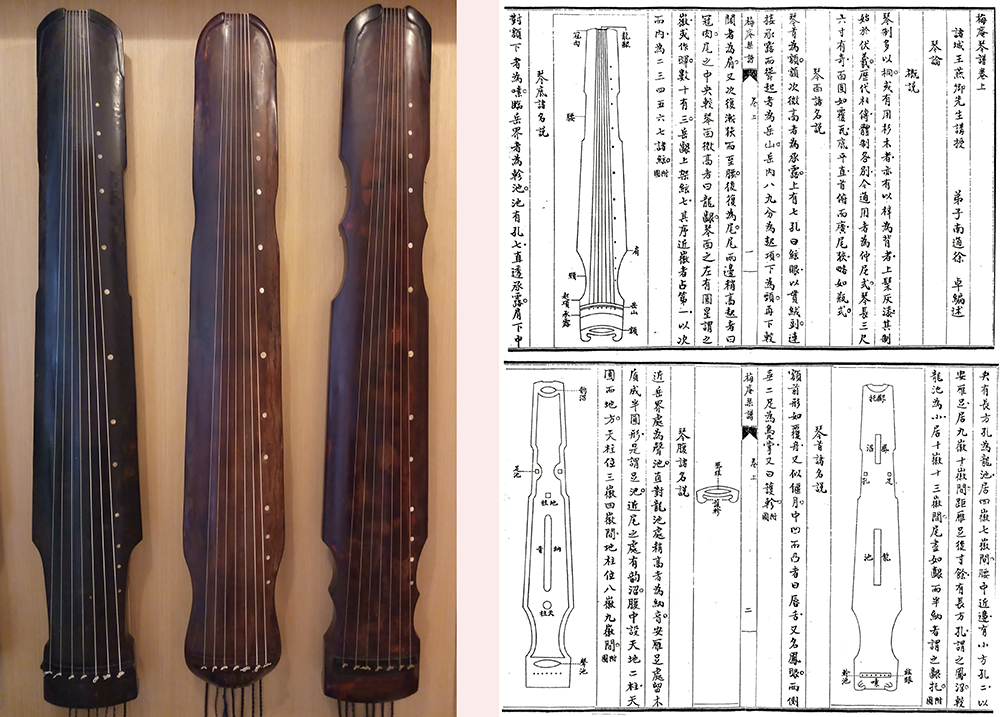

| Basic Structure of Guqin The guqin is often mixed up with the guzheng. Actually, the structure and sound of the two are quite different. The guzheng is bigger in size, usually has 21 strings, has movable bridges at the strings, and has a louder sound volume. The guqin is smaller in size, has seven strings without bridges so that the left-hand fingers can slide freely on the surface of the instrument, and has a softer sound volume. |

[Image 1](left)

Playing the guqin [Image 2](right)

Playing the guzheng  [Image 1] Playing the guqin  [Image 2] Playing the guzheng |

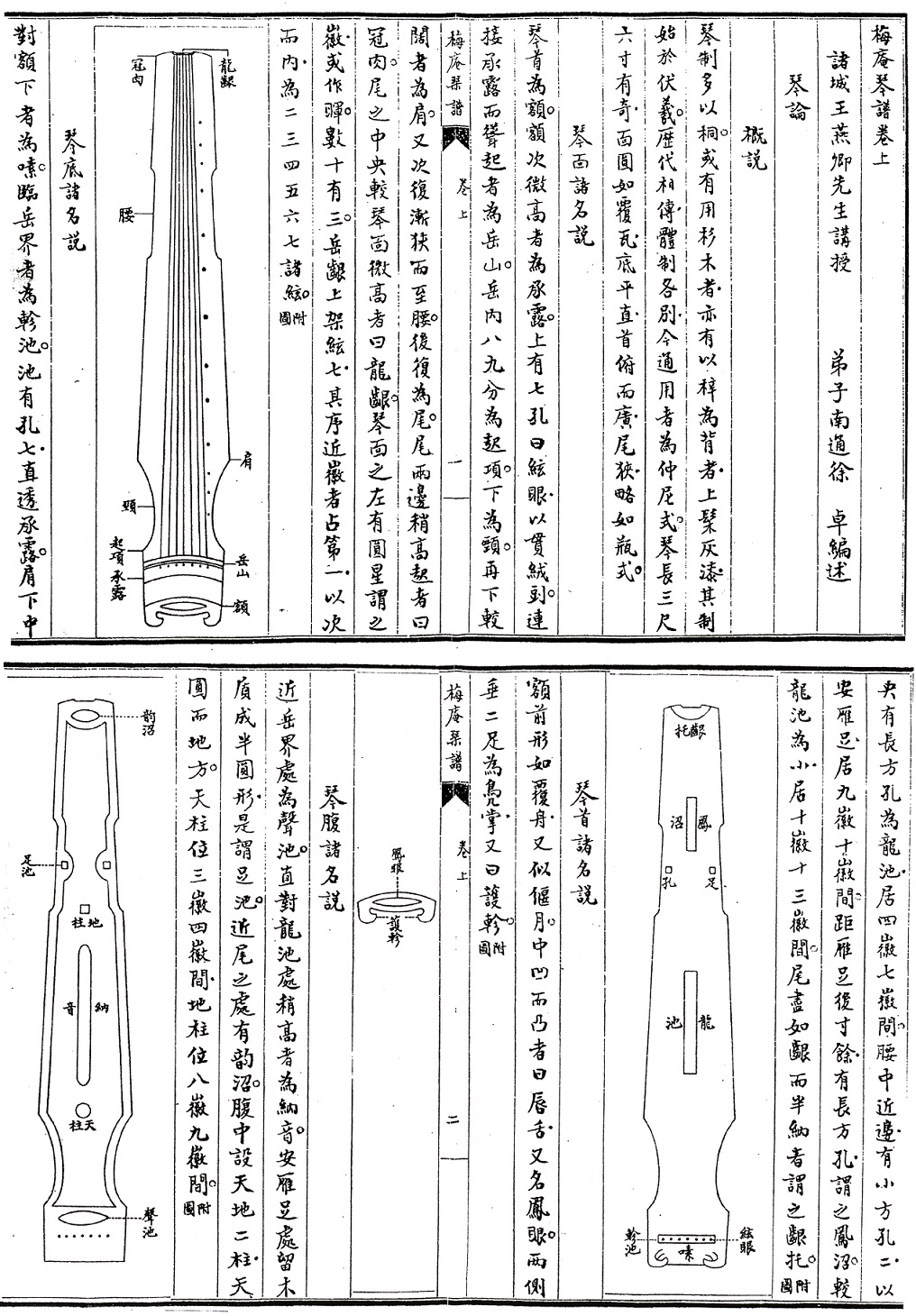

| The upper board of the guqin is usually made of Chinese parasol or Chinese fir. There are 13 studs on the upper board indicating the harmonic positions. The lower board is usually made of Chinese catalpa. Both boards are coated with cement and lacquer. There are a number of styles in guqin’s appearance. Different parts of the upper board, lower board and internal cavity are labelled with special names (detailed illustrations). |

[Image 3](left) Different styles of the guqin [Image 4](right) Names of various parts of the instrument, from Mei’an Qin Handbook of the early 20th century  [Image 3] Different styles of the guqin  [Image 4] Names of various parts of the instrument, from Mei’an Qin Handbook of the early 20th century |

A 3,000-year-old Musical Instrument for Literati’s Self-nurturing

The guqin is an important traditional musical instrument in China. The word qin (琴) in writings in the past specifically refers to this instrument. This word carries the general meaning of “musical instruments” only in modern times. This instrument has a history of 3,000 years, and past literature recorded that Confucius learned to play the guqin from Master Xiang. The structure of the instrument as we use today has already been fixed since the Wei and Jin period. In the past, the guqin was for self-nurturing by the literati, or for music sharing among a few close friends. It was not a popular instrument at the time and was primarily not for public performances. Over the years, upon transmission through generations of literati, special musical characteristics and aesthetic tastes have been developed for the instrument, which are quite different from those of the commonly heard traditional Chinese music, and are not easily comprehended. However, despite its lack of popularity, guqin music has flourished for 3,000 years, and is a gem among Chinese traditional arts.

The Importance of Guqin in Traditional Chinese Culture

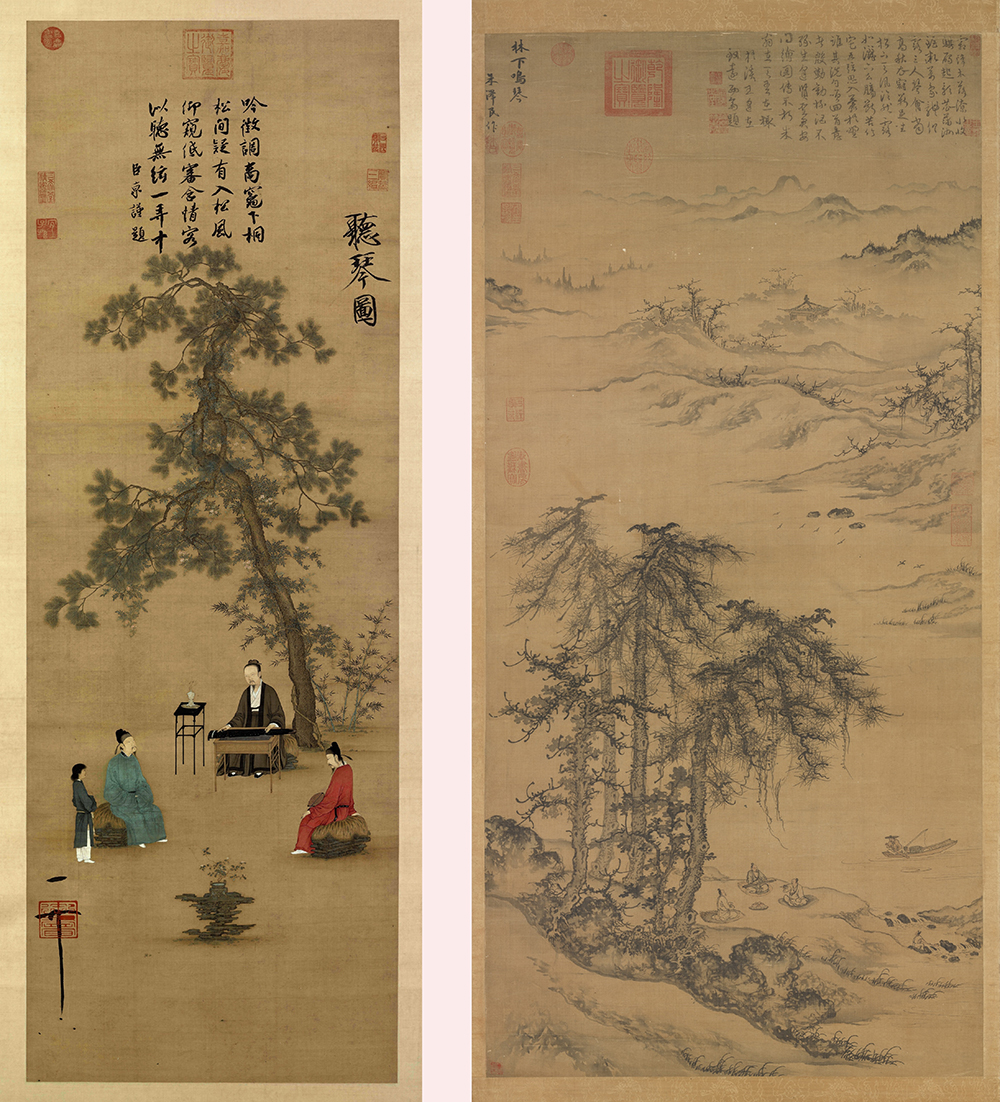

| World Cultural Heritage The guqin ranks first among the traditional four arts of Chinese literati, namely “guqin, chess, calligraphy and painting”. In 2003, its music was proclaimed as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by the UNESCO (i.e. the present Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity). Its selection as a world cultural heritage demonstrates its importance in traditional Chinese culture. Guqin in Poems and Paintings; Poems and Paintings in Guqin Music The guqin is the musical instrument that appeared most often in poems and paintings in the past, indicating the love towards the instrument among literati and artists. |

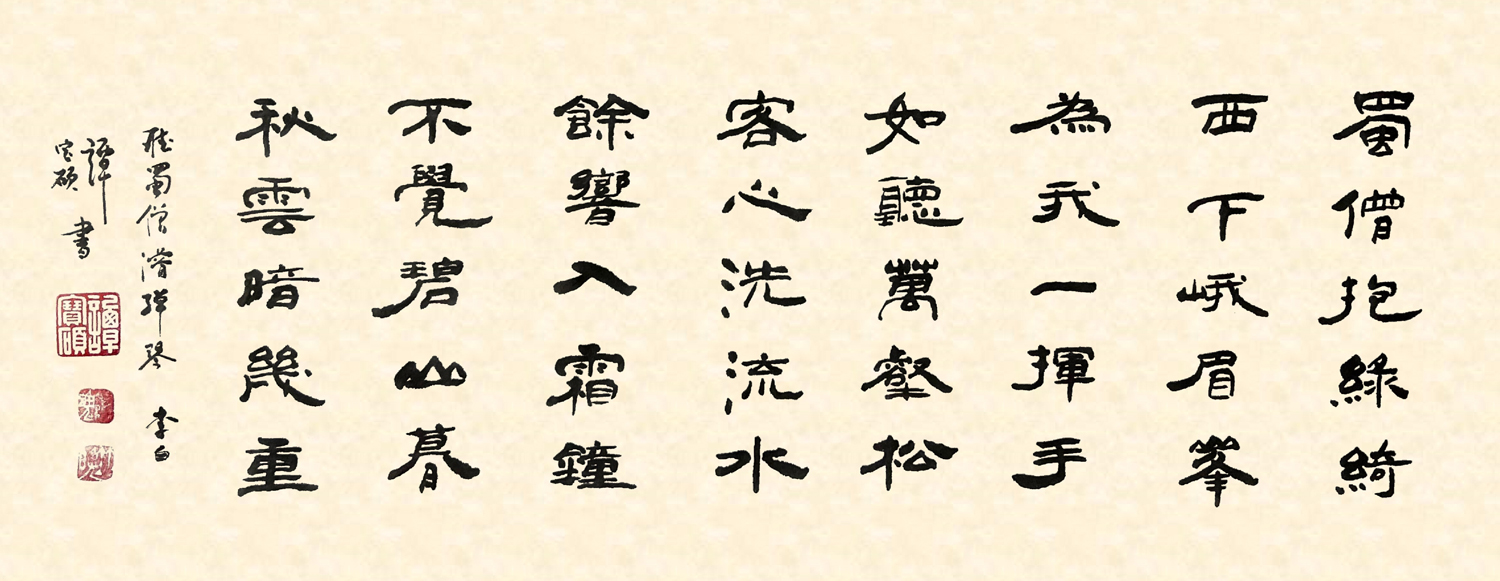

[Image 5] Monk Jun Playing the Lute (Qin) This is a well-known poem by Li Bai (701-762) of the Tang Dynasty:The monk from Sichuan carries his famous lute (qin), Coming down Mount Emei via the west route. With just one stroke he begins playing for me - Like whispering from thousands of pinetrees. It soothes, like a river running through my heart. The residual tones blend in with temple bells afar. Unknowingly the day on green hills has gone by. I gaze at autumn clouds piling up in the dark sky. |

[Image 6](left) Listening to the Qin by Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) of the Northern Song Dynasty [Image 7](right) Playing the Qin Under the Trees by Zhu Derun (1294-1365) of the Yuan Dynasty  [Image 6] Listening to the Qin by Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) of the Northern Song Dynasty  [Image 7] Playing the Qin Under the Trees by Zhu Derun (1294-1365) of the Yuan Dynasty |

[Image 8] A close-up of Playing the Qin Under the Trees |

| The mood expressed in guqin music is indeed that of poetry and paintings. Titles of guqin pieces are often related to mountains and rivers. The famous guqin piece Flowing Water was recommended by Chou Wen-chung (1923-2019), a renowned Chinese American musician, to represent Chinese music for inclusion in the Voyager Golden Record in the American spaceships sent to outer space in 1977, hoping that extraterrestrials who encounter the spaceships can understand the culture of our planet. Themes of guqin pieces are also often related to thoughts and feelings of the literati, for example, life of recluses in Dwelling in the Mountains and Dialogue Between the Fisherman and the Woodcutter, expression of sorrow in Lamenting the Past and Autumn Thoughts at Dongting Lake, ink painting in Wild Geese Descending on the Sandbank, longing for an old friend in Memories of an Old Friend, bidding farewell in Farewell at Yangguan, and historical events in The Guangling Suite. |

Playing and Characteristics of Guqin Music

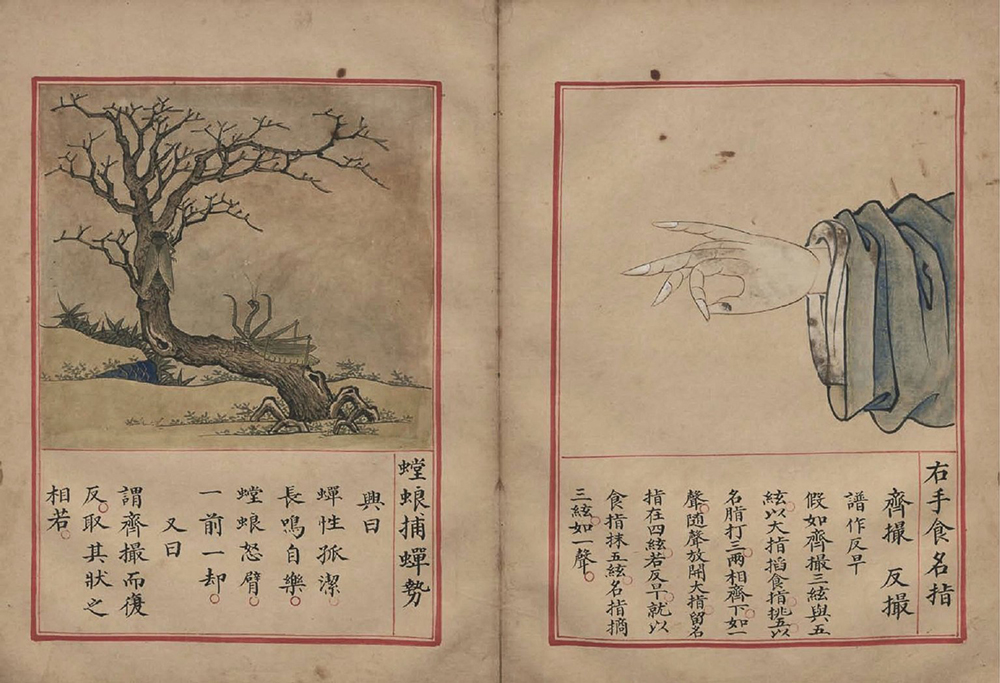

| Solo and Ensemble Lodge in Bamboo is a famous poem written by Wang Wei of the Tang Dynasty (618-907): I sit alone in a secluded bamboo grove, strumming my zither (qin), then whistling long. Deep in the woods - no one knows I am here, but the bright moon comes and shines on me. The guqin is usually used as a solo instrument. Traditionally, it can also be played with singing (video) or with the xiao, the vertical bamboo flute (video). Because of its soft sound volume, it is not easy for the guqin to play with instruments with louder sound volume. However, modern sound amplification system increases the possibility of ensemble playing with other musical instruments (video). Posture and Fingering The guqin is an instrument for self-nurturing, and the emotion expressed is restrained. When playing the guqin, it is important to have a relaxed posture without unnecessary bodily movements. There is a large variety of fingering techniques, and fine control of finger movements is required. Many old guqin handbooks give detailed explanation and diagrams about the fingering techniques. |

||||||||||||

[Image 9] Diagrams explaining a fingering technique, from a Ming Dynasty handbook Music Bequeathed from Antiquity |

||||||||||||

| Refined and Varying Tone Colour and Rhythm There are three ways of sound production in the guqin:

|

||||||||||||

Different ways of sound production can be utilised in different sections of a guqin piece. For example, the opening section of the famous Three Variations on the Plum Blossom (video) is played with open string notes, while sections two, four and six are all in harmonic notes. Such changes and contrasts in tone colour can also be used in different musical phrases, as well as interpolated in a single phrase (video), bringing out an interesting effect. The rhythm of guqin music also has special characteristics. A piece usually starts slowly in free rhythm and low density, followed by inconspicuous acceleration. There are usually no regular cycles of strong and weak beats, leading to an unconstrained feeling. The piece is developed as an integrated whole, with gradually increasing tension, and returns to slow free rhythm at the end. Aesthetic and Philosophical Perspectives Through variations in tone colour and rhythm, the guqin player pursues the restrained mood of poetry and paintings. Emotions expressed are also influenced by Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist ideologies. As exemplified by Tune for a Pleasant Evening (video), many pieces are serene and subtle. But, similar to traditional poetry, many other styles are possible, for example the lively Drunken Elation (video) and the passionate The Guangling Suite (video). However, the main aesthetic perspective of guqin music is its comparatively restrained way of expression, as reflected in The Xishan Treatise on the Aesthetics of Qin Music of the late Ming Dynasty, which states that “one should not indulge excessively in the intensity of musical interest” and “rapidity is fast but not chaotic. It should be able to depict the sound of a mountain-slide or a roaring waterfall with a leisurely mood.” |

Uniqueness of Guqin Scores

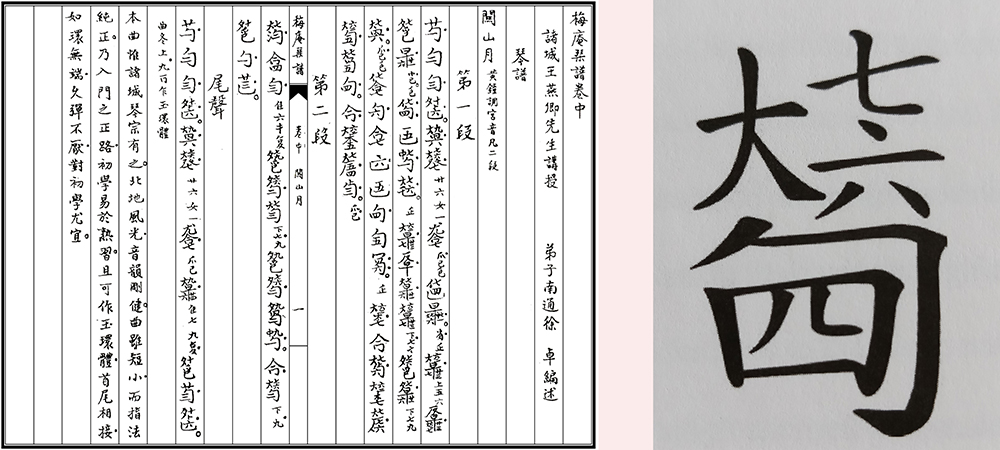

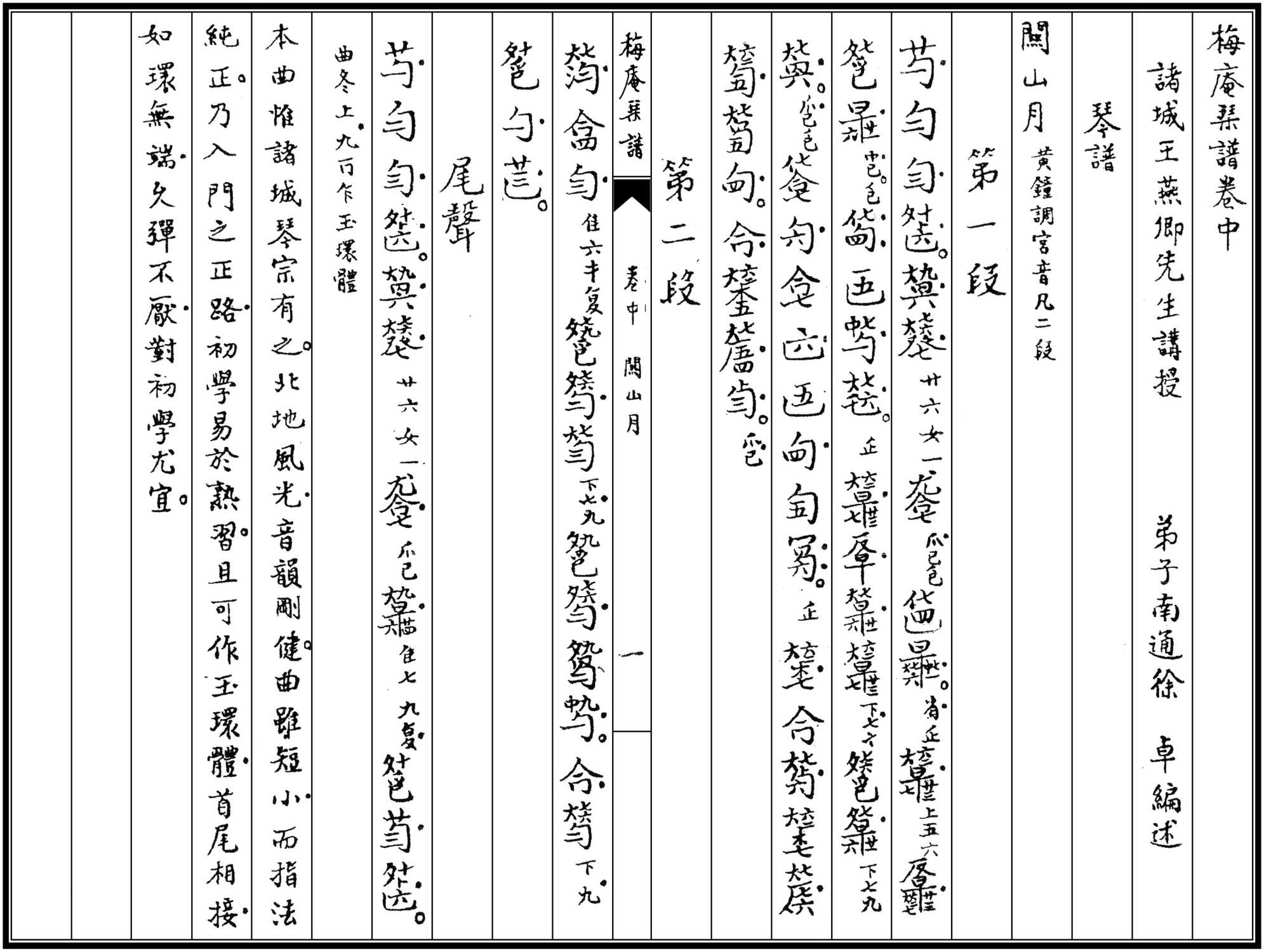

| Extant Guqin Scores With the development of the special tablature notation, many guqin pieces in the past can be passed down to the present day. There are over a hundred guqin handbooks surviving from previous centuries, containing nearly 3,000 pieces in different versions. The tablature score does not directly notate the musical notes. Instead, the instructions on fingering technique, the finger position and the string to be plucked are combined into a tablature in a simplified format. Musical notes will be produced when the player follows the instructions embedded in the tablature. Such notation reflects the importance of fingering and tone colour in guqin music. |

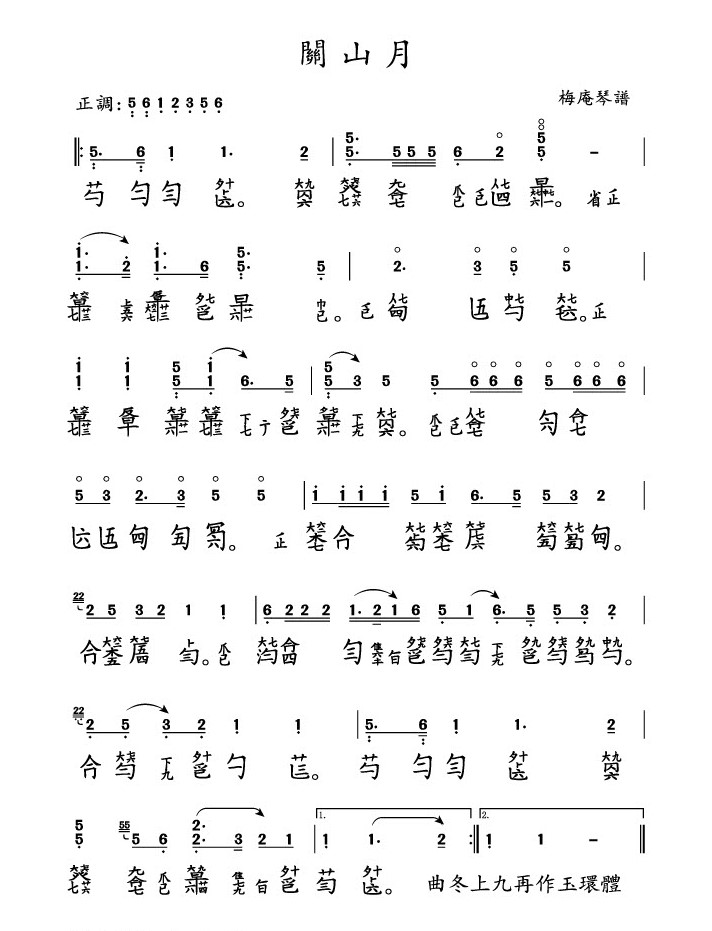

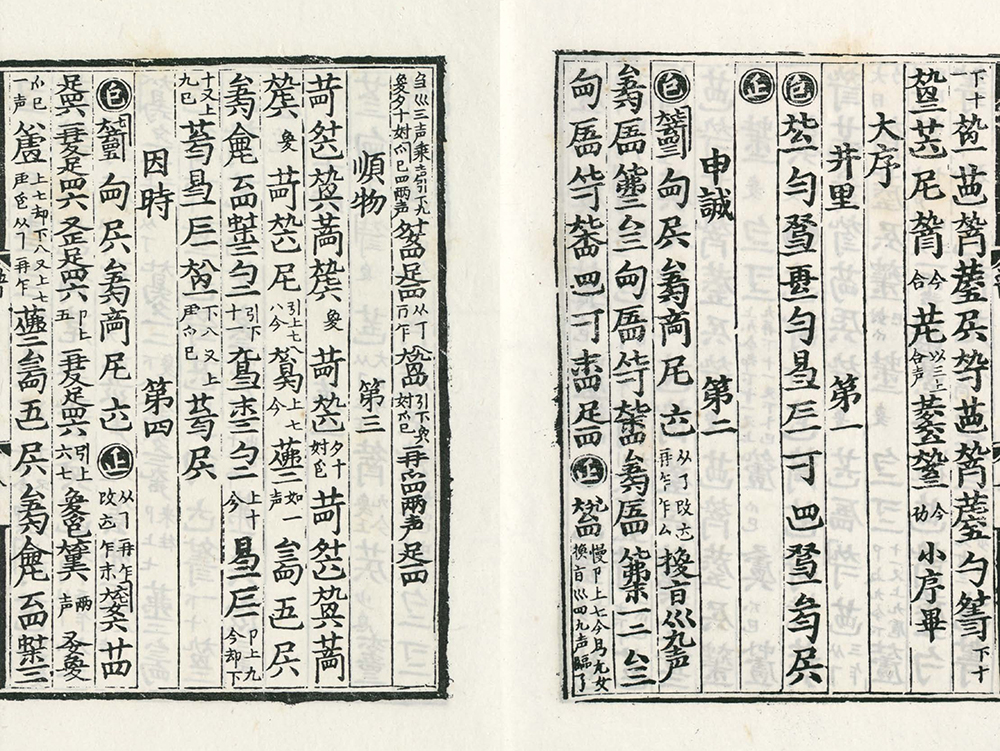

[Image 10](left) Tablature score of The Moon Over Mountain Guan, from Mei’an Qin Handbook of the early 20th century [Image 11](right) The upper part of the tablature indicates that the left thumb (大) presses at position 7.6 (七六) near to the 7th stud. The lower part of the tablature indicates that the right middle finger plucks (勹) the 4th string (四) in an inward direction.  [Image 10] Tablature score of The Moon Over Mountain Guan, from Mei’an Qin Handbook of the early 20th century  [Image 11] The upper part of the tablature indicates that the left thumb (大) presses at position 7.6 (七六) near to the 7th stud. The lower part of the tablature indicates that the right middle finger plucks (勹) the 4th string (四) in an inward direction. |

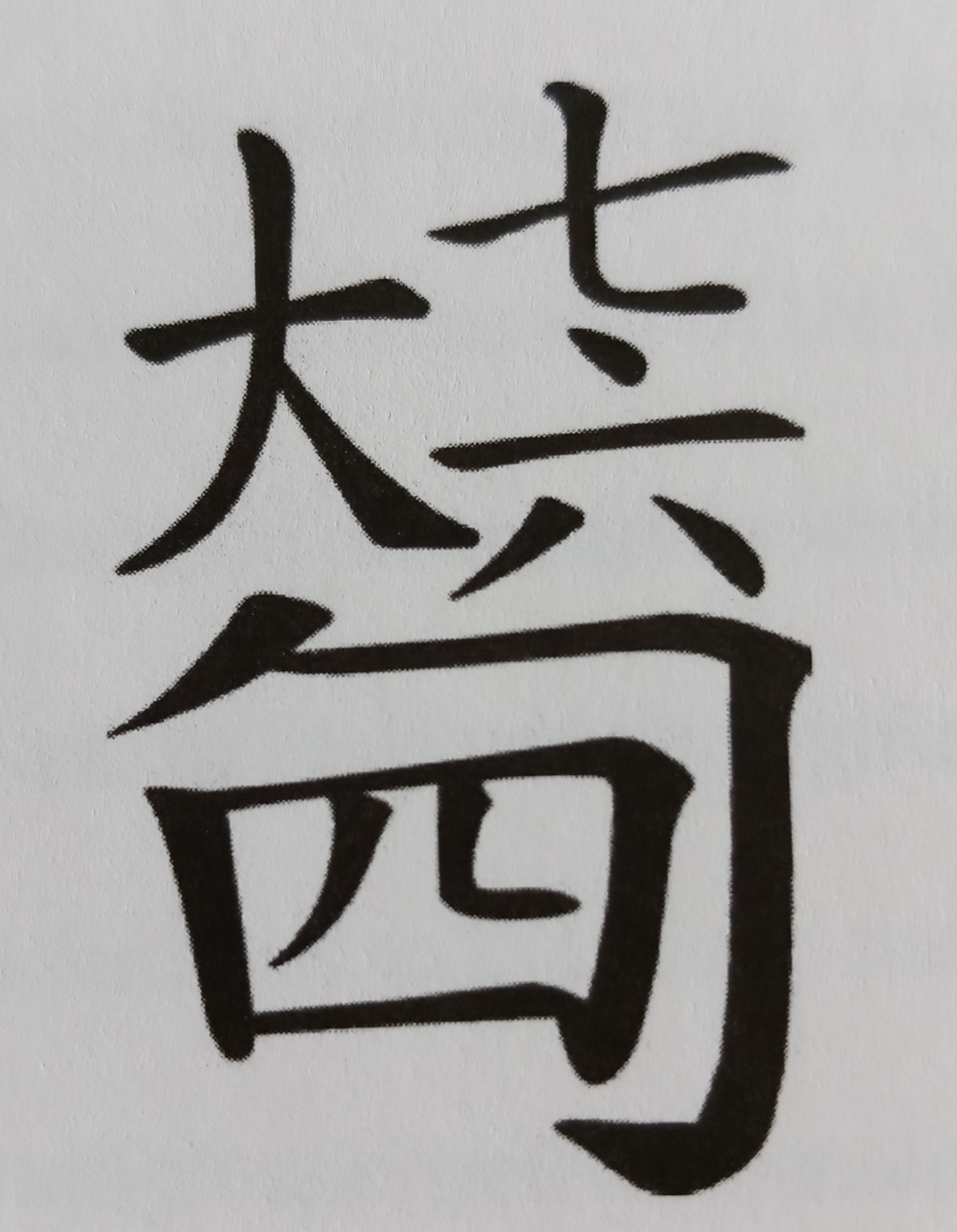

| Rhythm was not notated in the traditional tablature score. It was passed down only orally. In recent times, in order to facilitate learning and transmission, a “parallel” score has been developed, in which the tablature score is written in parallel with staff notation or cipher notation. |

[Image 12] A modern “parallel” score of The Moon Over Mountain Guan, in which the tablature score is written in parallel with cipher notation. (video) |

| What is dapu? Many surviving old guqin scores are no longer played. The tablatures and fingering of these old scores may be different from those of the more recent ones, and the rhythmic elements are not notated. Faced with these scores with an interrupted transmission, guqin players have to make a detailed study and to re-create the rhythm before the piece can be played again. This process of reconstruction is called dapu. Important examples of dapu in the last century include Drunken Elation (video) and The Guangling Suite (video). |

[Image 13] Score of The Guangling Suite, from The Mysterious and Fantastic Handbook (1425) |

The Instrument and Its Construction

| Historical Artifacts Surviving guqins with a long history are invaluable pieces of antique. Several Tang Dynasty guqins are kept in the Palace Museum in Beijing. There are a lot of private collectors owning guqins from the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties. Many of the antique guqins can be played after restoration. Because the wood and lacquer cement are aged, many antique guqins have better sound quality than the newly made ones. |

||||||||

[Image 14] Cracks developed on the lacquer surface of an antique guqin over the years. |

||||||||

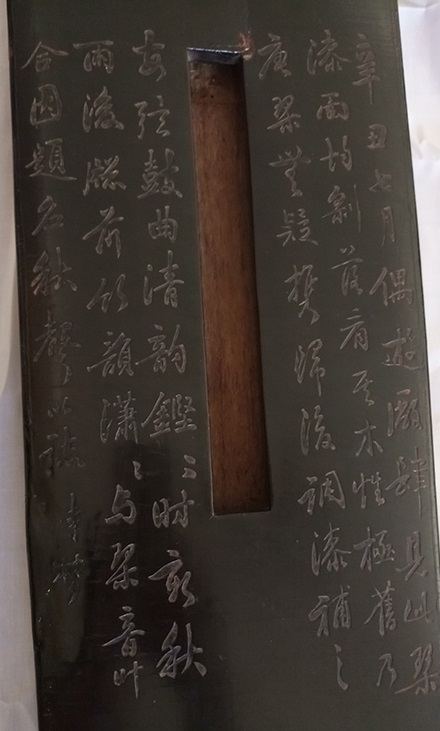

[Image 15](left) The history of an antique guqin can be seen from the inscriptions on the lower board. [Image 16](right) The name of antique guqin was usually carved above the inscription on the lower board.  [Image 15] The history of an antique guqin can be seen from the inscriptions on the lower board.  [Image 16] The name of antique guqin was usually carved above the inscription on the lower board. |

||||||||

| Silk and Metal Strings Silk strings of traditional Chinese bowed-string and plucked-string instruments were comprehensively replaced by metal strings in the last century. The guqin is no exception. Compared to silk strings, metal ones produce a brighter and louder sound with a more stable tuning, and are less easy to break. However, a number of guqin players in Hong Kong still use silk strings for the more mellow tone. In the latter half of the last century, the production of silk strings nearly ceased. Fortunately, through the effort of a dedicated few, the production of high-quality silk strings finally resumed, which caused more and more players in the Mainland choose the silk strings again. Strings used in the demonstration videos are as follows:

|

||||||||

Steps in Guqin Making The construction of the guqin is a refined handicraft. Starting with selection of appropriate pieces of wood, it involves many steps of work, including chopping, hollowing, fitting, assembling, cement priming, sanding and lacquering. In addition to professional guqin makers, some guqin players also make instruments for their own use. |

||||||||

[Image 17] Hollowing: The inner side of the upper board is hollowed out with different chisels. (Demonstration by Choi Chang-sau)  [Image 18] Fitting: Hardwood accessories are installed on the hollowed and conditioned body. |

||||||||

[Image 19] Assembling: The chopped and hollowed top and bottom boards are sticked together with a mixture of raw lacquer and flour, or with animal gum.  [Image 20] Sanding: After completing the wood base and priming the lacquer cement, repeated sanding on the surface of the guqin is required. |

Guqin Culture in Hong Kong

| Traditional Chinese culture clashed with Western culture in the 20th century. Fortunately, through the effort of the past generations of guqin players, guqin culture managed to be maintained and developed. Important transmission lineages also came into existence in Hong Kong. The most important guqin teacher in Hong Kong in the last century was Tsar Teh-yun (1905-2007). Many of her students are influential in Hong Kong and overseas. Other promoters in Hong Kong currently include Tong Kin-woon (1946- ) and his students; Yao Gongbai (1948- ), a representative exponent of intangible cultural heritage at national level, who resides in Hong Kong recently; and the Hong Kong Yung’s family. The development of guqin music in Hong Kong is slightly different from that in the Mainland. Here, post-secondary music students majoring in guqin performance are very rare. Most players are amateurs. In order to maintain the guqin culture, players in Hong Kong participate actively in reconstruction of old scores, compositions, researches, publications, instrument making, silk string making, etc. The heritage of guqin making in Hong Kong is also significant. Choi Chang-sau (original name: Lau Chang-sau, 1934- ) is a rare specialist in guqin making in Hong Kong, and is a representative exponent of intangible cultural heritage at national level. In the past 30 years, he has been dedicated to passing the art of guqin making to amateur players, so that they can make or repair their own instruments. The Arts of the Guqin (the Craft of Qin Making) is one of the items on The Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong (detailed information). To learn more, please browse the “Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Database” (website) of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office. |

Contemporary Development of Guqin

| The precious cultural heritage of the guqin is evolving, not just kept rigidly in the museum. Guqin pieces of the past have undergone changes during the transmission process, and developed into different versions. Composing new pieces based on traditional elements has also been a way of development. Among the demonstration pieces in this exhibition, Capriccio on the Town of Wei (video) and Three Poems by the Drunken Li Bai (video) are new compositions by Hong Kong players. In the 21st century, there has been a rapid surge of guqin activities in the Mainland. In some large cities, playing the guqin has become an identity merging the traditional and the fashionable. Attempts to use the instrument to play pop music, modern music, or concerto pieces with a large orchestra began to appear. However, we must remember that the old and the new are interconnected in many aspects. Having been nurtured over the past thousands of years, the ways of playing, aesthetic perspectives, quality repertoire and integration with other Chinese traditional cultures, are the most precious aspects of the guqin culture. Contemporary guqin players, while attempting to achieve breakthroughs, must maintain an insistence on upholding the treasures of the tradition. We first need to inherit the past, before we can explore the future. |

Demonstration Videos

|

Three Variations on the Plum Blossom

Passed down by Tsar Teh-yun This was originally a dizi piece associated with Huan Yi of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420). It was later arranged for the guqin in the Tang Dynasty, and had become a favourite piece among guqin players ever since. The music describes the loftiness and pureness of plum blossom. The “three variations” in the title refers to the three times the harmonic section played, progressing from tranquility to brightness. These three sections start at 1:16, 2:10 and 3:51 respectively in the video. Guqin (silk strings): John Yiu Shek-on |

|

The Moon Over Mountain Guan

Mei’an Qin Handbook (1931) This short piece reflects the spirit and emotions of the poem of the same title by Li Bai, depicting the sufferings of war in ancient times. Different ways of sound production are used in different musical phrases, as well as interpolated in a single phrase, bringing out characteristic tone colour effects. Guqin (silk strings): Wong Chun-fung Xiao: Ken Wu Yun-kan |

|

Tune for a Pleasant Evening

Passed down by Tsar Teh-yun The piece has been popular since its first publication in a late Ming Dynasty guqin handbook. With the frequent use of soft sliding tones, the music depicts a relaxed atmosphere of a pleasant evening meeting with good friends, bringing out a subtle and serene poetic mood. Guqin (silk strings): John Yiu Shek-on |

|

Drunken Elation

The Mysterious and Fantastic Handbook (1425) Reconstructed by Yao Bingyan This piece was attributed to Ruan Ji (210-263), one of the “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove”. The music was reconstructed by famous guqin player Yao Bingyan (1921-1983) in the 20th century. It is a short and lively piece, depicting a literatus trying to escape from precarious politics by indulging in wine. Guqin (silk strings): Wong Chun-fung |

|

The Guangling Suite

The Mysterious and Fantastic Handbook (1425) Reconstructed by Wu Jinglue The piece can be dated back to the late Han Dynasty. Ji Kang, a famous literatus of the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280), was well-known for playing this piece. It is about the story of “The Assassination of Emperor Han by Nie Zheng”. The music demonstrates a dramatic interplay between the tragic and intense, and the soft and moving, exemplifying the emotions and grandeur of a complex guqin composition. The piece was reconstructed by famous guqin player Wu Jinglue in 1954. It is originally well over 10 minutes long. This demonstration is an abridged version. Guqin (metal strings): Wang Youdi |

|

Capriccio on the Town of Wei

Wang Youdi (2019) This composition is based on the poem Bidding Farewell to My Friend Travelling Westward by Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei. Utilising the special characteristics of the guqin and dizi, the piece fuses the musical features of the Western Regions with those of the guqin piece Farewell at Yangguan, painting an endless and fascinating view of the western terrain. Guqin (metal strings): Wang Youdi Dizi: Jiang Ning |

|

Three Poems by the Drunken Li Bai (excerpt)

Tse Chun-yan (2017) This piece depicts Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai writing a set of three famous poems The Tune of Qingping while drunk for Emperor Xuanzong and Lady Yang during their visit to the peony garden. The poems were then set to music and sung by the court musician Li Guinian. A special hemitonic pentatonic scale found in past court music is intermittently used in the guqin and xiao parts, creating an interesting contrast to the elegant main melody. Vocal: Chan Chak-lui Guqin (silk strings): Tse Chun-yan Xiao: Ken Wu Yun-kan |